Sandeha Nivarini

Sandeha Nivarini

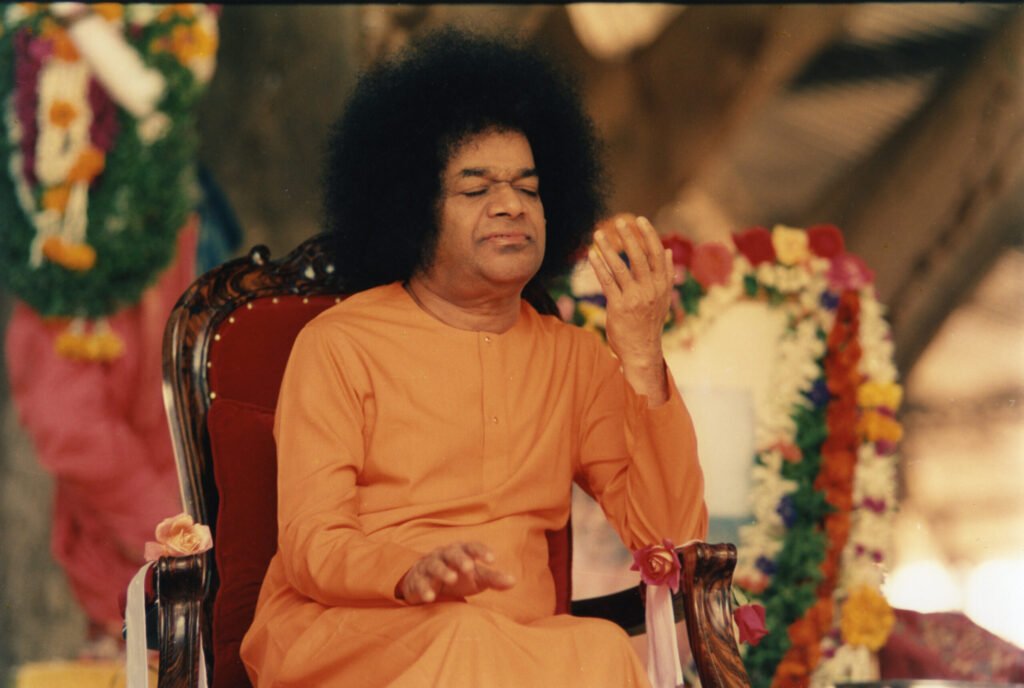

Sri Sathya Sai Baba’s Sandeha Nivarini, meaning “The Removal of Doubts,” is a jewel among his writings, for it speaks directly to the seeker’s heart. Unlike narrative works such as Ramakatha Rasavahini or reflective treatises like Jnana Vahini, this text is structured as a dialogue between Baba and an earnest devotee. The devotee represents all spiritual aspirants—filled with questions, confusions, and longings—while Baba patiently answers, guiding with love and clarity. Each doubt addressed is not a casual curiosity but a profound inquiry into the nature of God, the self, devotion, and liberation. In resolving these doubts, Baba does not merely give intellectual explanations; he transforms the seeker’s vision, lifting thought from the narrow human perspective to the universal divine standpoint.

At the outset, the devotee asks whether God truly takes form as Avatar. Baba responds with gentle firmness: yes, God assumes human form whenever Dharma declines, as proclaimed in the Bhagavad Gita. Just as the ocean takes the form of waves without losing its essence, the infinite Divine assumes a finite body for the sake of humanity without ceasing to be infinite. Baba explains that the Avatar is not limited by the body but uses it as an instrument to teach, guide, and protect devotees. For the common man who cannot comprehend the formless Absolute, God in human form becomes accessible, relatable, and lovable. Thus, the first great doubt is dissolved: divinity does indeed walk the earth in the guise of man, and to recognize and revere the Avatar is itself a path to liberation.

Another central question concerns the relationship between the individual soul (jiva) and the Supreme Self (Paramatma). The devotee wonders: are they separate, or are they one? Baba’s answer is both simple and profound. He explains that the jiva is like a spark from the fire of Paramatma. In essence, both are of the same nature—pure, eternal, and divine—but due to ignorance and attachment, the jiva identifies with the body and mind and imagines itself separate. When this ignorance is removed, the jiva realizes that it has always been one with the Supreme. Baba illustrates with metaphors: the space in a pot seems different from the vast sky outside, but when the pot breaks, the space is seen as one; similarly, when the ego dissolves, the individual merges with the infinite. The removal of this doubt is crucial, for it shifts the seeker’s identity from the perishable body to the eternal Self.

The devotee also asks: how should one practice devotion (bhakti)? Baba replies that true devotion is not mere ritual or mechanical repetition but constant remembrance of God with love. He insists that devotion must be steady, like a lamp protected from the wind, not wavering with circumstances. Singing God’s name, serving others selflessly, and keeping company with the good are practical ways to cultivate devotion. Yet devotion is not separate from knowledge and action: real bhakti naturally leads to wisdom (jnana) and righteous conduct (karma). Baba teaches that all paths—bhakti, jnana, karma—are interconnected, and whichever path is sincerely followed with love will lead to the goal. The essence of bhakti, he says, is surrender: giving up the sense of “I” and “mine” and living as an instrument of God’s will.

The text also addresses doubts about liberation (moksha). What is liberation, and how can one attain it? Baba explains that liberation is not a physical place to be reached but a state of freedom from bondage. To be liberated is to know one’s true nature as the Atma, beyond birth and death. Just as waking frees a dreamer from the sorrows of a dream, realization frees the soul from the illusions of worldly life. Liberation is attained not by escaping the world but by living in it without attachment, like a lotus on water. Baba assures that liberation is not reserved for ascetics alone; every householder, every worker, every devotee can attain it by living in love, practicing truth, and surrendering to God. Thus, the fear that moksha is distant or difficult is lovingly dispelled.

One striking feature of Sandeha Nivarini is Baba’s emphasis on practice over theory. The devotee raises intellectual questions—about scriptures, rituals, and philosophy—but Baba consistently turns the focus to daily life. He explains that reading sacred texts is good, but without practicing their teachings, it is like counting other people’s cows. He stresses that truth, nonviolence, love, and self-control are the real marks of spirituality. In this way, he clears the common doubt: is spirituality separate from life? His answer is clear: spirituality is life itself, lived with awareness of God.

A particularly touching moment arises when the devotee asks how one may know if God is pleased with them. Baba replies that God’s grace is reflected in the peace of the heart. If a person feels inner calm, love toward all, and freedom from selfish desire, then surely God’s presence is guiding them. Conversely, if restlessness, hatred, or pride dominate, then one must correct their course. Baba emphasizes that God is not an external judge handing out rewards and punishments; He is the indwelling witness, the conscience within. To follow that inner voice is to live in harmony with Him.

The text also tackles the question of suffering. Why does suffering exist if God is merciful? Baba explains that suffering is the result of past actions, governed by the law of karma. God does not create pain to punish; He allows karma to unfold so that the soul may learn and evolve. Suffering is therefore a teacher, an opportunity to develop patience, strength, and detachment. Yet God’s grace can soften or even remove the effects of karma when one turns sincerely to Him. Thus, the apparent contradiction between divine mercy and human suffering is resolved: both operate hand in hand, leading the soul toward growth.

Throughout Sandeha Nivarini, Baba’s style is warm, clear, and practical. He does not dismiss doubts as weakness but honors them as steps toward understanding. He encourages seekers to question sincerely, for only then can faith mature into conviction. At the same time, he warns against endless intellectual speculation, which leads to confusion; real clarity comes only through practice and inner experience. His answers are never abstract philosophy but concrete guidance on how to live: control the senses, speak truth, serve others, love God, and surrender the ego.

The beauty of this Vahini lies in its universality. Though rooted in Vedantic wisdom, Baba’s answers are relevant to people of all backgrounds. Whether one is a scholar or a simple devotee, the truths apply equally: God is within, love is the path, and selflessness is the goal. The dialogue format makes the teaching personal and intimate, as though Baba himself is sitting before the reader, patiently clearing each doubt.

In conclusion, Sandeha Nivarini is a bridge between confusion and clarity, between questioning and conviction, between seeker and master. It demonstrates that doubts are not obstacles but stepping stones when brought with humility to the feet of wisdom. Baba, as the compassionate teacher, transforms uncertainty into understanding and fear into faith. He assures seekers that the journey to God is not distant but begins here and now, with the purification of thought, word, and deed. The central message shines clearly: you are not the body or the mind but the eternal Atma, one with God; live in love, practice truth, and all doubts will dissolve like mist before the rising sun. Thus, Sandeha Nivarini is not merely the removal of doubts but the awakening of vision, enabling the devotee to walk with confidence, devotion, and joy on the path to liberation.