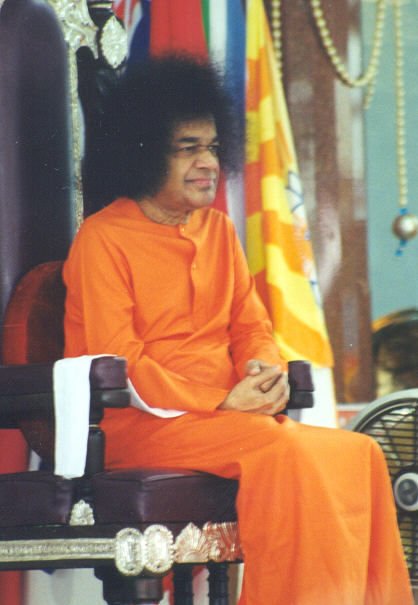

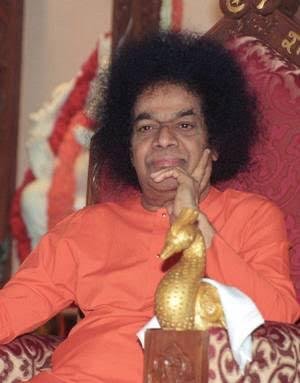

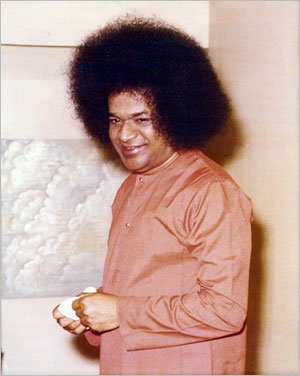

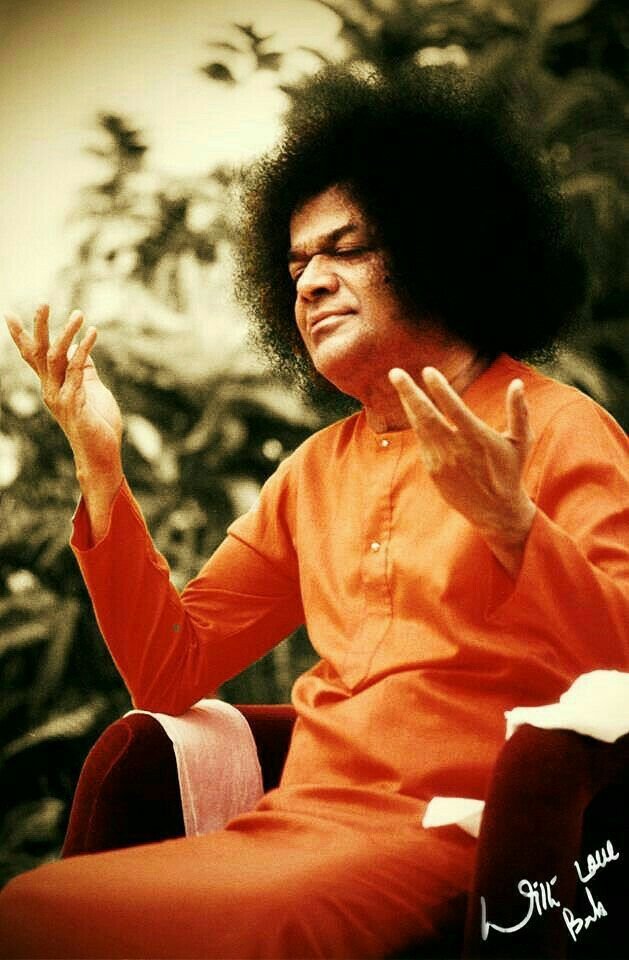

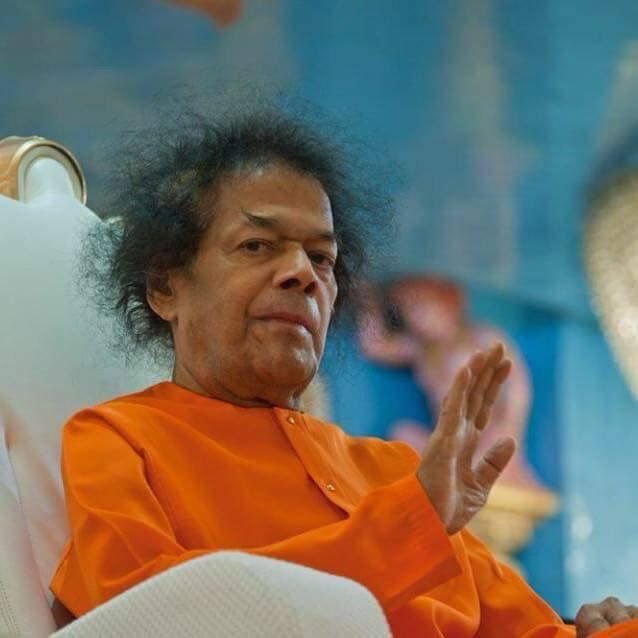

Dhyana Vahini

Dhyana Vahini

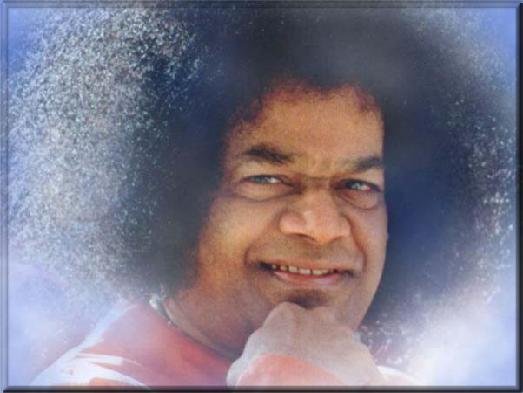

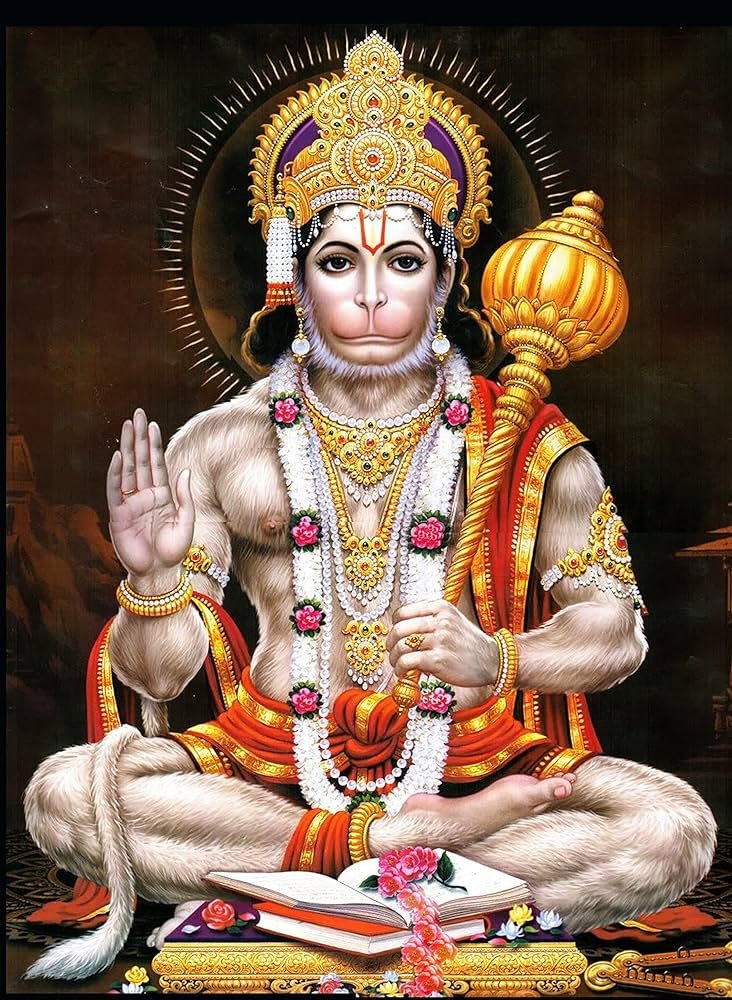

Sri Sathya Sai Baba’s Dhyana Vahini, meaning “the Stream of Meditation,” is a spiritual manual that gently but firmly guides the seeker into the heart of meditation, showing that the practice is not merely a technique to be performed at certain times of the day, but a continuous way of life, an inner discipline that transforms the mind and awakens the soul to its divine reality. In this text, Baba explains that meditation is the royal road to self-realization, the process through which the restless mind is stilled, the senses are mastered, and the individual consciousness merges with the universal consciousness. The book begins with a simple but profound insight: that the human mind, left unregulated, is like a monkey jumping from branch to branch, distracted, restless, and constantly craving. Just as a lamp flickers in the wind, the mind cannot hold a steady flame of awareness until it is sheltered and trained. Meditation, therefore, is the art of creating that shelter, of calming the winds of desire and fear, of steadying the flame of inner awareness so that it may shine clearly upon the Self. Baba emphasizes that meditation is not escapism or withdrawal from life, but rather the most practical way of engaging with life, for only a mind anchored in peace can act with clarity, compassion, and righteousness. He urges seekers to see meditation as food for the soul, as essential as bread is for the body and air is for the lungs.

One of the most striking teachings in Dhyana Vahini is Baba’s emphasis on purity—purity of thought, word, and deed—as the foundation of successful meditation. He explains that the mind cannot be forced into silence if it is burdened with guilt, deceit, or selfishness. Just as dirty water cannot reflect the moon, a mind clouded by impurity cannot reflect the light of the Self. Therefore, the preliminary discipline of the seeker must be to live a life of truth, non-violence, compassion, and self-control. Baba insists that meditation is not a mechanical exercise of sitting cross-legged with eyes closed, but the culmination of a moral and spiritual life. To meditate while living an unrighteous life is like pouring water into a leaking pot—it yields little fruit. The seeker must first cultivate detachment, reducing unnecessary desires and attachments, so that the mind is freed from constant agitation. Baba compares the mind to a lake: when it is disturbed by winds and waves, one cannot see the bottom; but when it is still, the depths are revealed. In the same way, when the lake of the mind is stilled through discipline and purity, the depth of the Self is revealed in meditation.

Baba also outlines the actual process of meditation in simple but powerful terms. He recommends beginning with concentration—focusing the mind on a sacred form, a divine name, or the breath—until the wandering tendencies of the mind are gradually overcome. Concentration leads to contemplation, where the seeker begins to dwell deeply on the qualities of the Divine, such as love, compassion, wisdom, and bliss. Finally, contemplation matures into true meditation (dhyana), where the duality of meditator and object dissolves, and there remains only pure awareness, unbroken and luminous. In this state, the seeker experiences the truth of the Upanishadic declaration, “Aham Brahmasmi” (I am Brahman). Baba stresses that this journey requires patience and perseverance, for the mind does not submit easily; it must be trained gently but firmly, with faith and persistence. Just as a gardener waters a seed daily without expecting instant fruit, the seeker must practice meditation daily with devotion, trusting that the results will unfold in their own time.

An important aspect of Dhyana Vahini is its insistence that meditation is not reserved for monks, ascetics, or those who have renounced the world. Every person, whether householder or student, worker or leader, has the capacity and the responsibility to practice meditation. Baba teaches that even a few minutes of sincere meditation daily can transform one’s character, bringing inner strength, serenity, and compassion. The test of meditation is not in the experience on the meditation mat but in daily life: does the seeker emerge from meditation more patient, more truthful, more loving, and more balanced? If not, then something is lacking. In this way, meditation becomes not an isolated activity but the very rhythm of life, infusing work, family, and society with peace and harmony. Baba reminds us that meditation is the direct path to God because it bypasses intellectual debate and ritual complexity, plunging directly into the experience of the Self. Scriptures, teachers, and rituals are helpful, but in meditation the seeker experiences truth firsthand, like tasting sugar instead of reading about it.

The universality of Baba’s message shines through Dhyana Vahini. He explains that meditation is not bound to any religion, culture, or creed; it is the birthright of every human being. Christians may meditate on Christ, Muslims on Allah, Hindus on Rama or Krishna, Buddhists on the Buddha, yet all are traveling the same inner road to the same eternal Self. What matters is not the form but the depth of concentration and the purity of heart. Baba urges seekers not to waste time arguing over sectarian differences but to plunge into practice, for only practice yields realization. He also warns against the common pitfalls of meditation: impatience, pride, and escapism. Impatience arises when the seeker expects instant visions or powers; pride arises when one boasts of meditation experiences; escapism arises when meditation is used to avoid worldly duties. True meditation, he says, makes a person more humble, more eager to serve, and more committed to dharma, not less.

Perhaps the most beautiful teaching of Dhyana Vahini is the assurance that meditation reveals the natural bliss of the soul. Baba explains that every human being is in search of happiness, but most search outside in wealth, pleasure, or fame. Yet these bring only fleeting satisfaction, followed by restlessness. Meditation turns the search inward, where the infinite source of bliss already resides. When the mind becomes still, this bliss rises naturally, just as the sun emerges when clouds disperse. This bliss is not dependent on circumstances, possessions, or relationships; it is the inherent nature of the Self. To live in that bliss is to be truly free. Baba calls this the state of liberation (moksha), where one realizes one’s oneness with God and lives in constant awareness of love and peace. The fruits of meditation are thus not only personal joy but also universal harmony, for a person established in meditation radiates peace to the world like a lamp radiates light. Such a person becomes a blessing to family, society, and humanity.

In conclusion, Dhyana Vahini is not a theoretical treatise but a practical manual, a flowing stream of wisdom that washes away confusion and nourishes the roots of spiritual life. Baba takes the lofty philosophy of the Upanishads and the Gita and translates it into simple, actionable guidance for modern seekers. He shows that meditation is not something exotic, difficult, or reserved for a few, but the most natural and essential expression of human life. He teaches that meditation begins with purity, deepens with practice, blossoms into bliss, and culminates in union with God. In its pages, one feels both the authority of timeless wisdom and the tenderness of a loving teacher. Ultimately, the book calls us not merely to read about meditation but to practice it daily, to make life itself a meditation, and to discover in the silence of the heart the eternal voice of the Divine. Thus, Dhyana Vahini is both a lamp and a path—a lamp that illuminates the darkness of ignorance, and a path that leads the seeker to the infinite light within.